The Great Katmai Eruption of 1912: A Century of Research Tracks Progress in Volcano Science

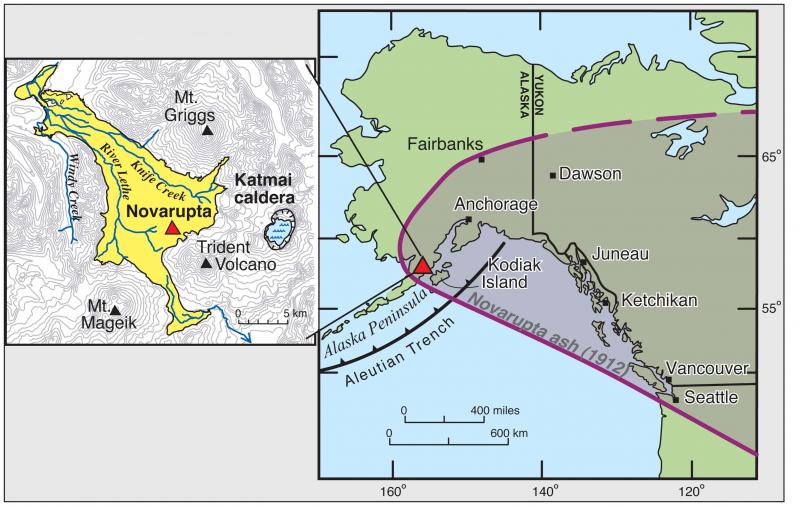

The pyroclastic outburst at Novarupta (Alaska) in June 1912 was the 20th century's most voluminous volcanic eruption (Figure 1). Marking its centennial, we summarize the unusual eruptive sequence, which was long misattributed to nearby Mount Katmai, and how its deposits have provided key insights about volcanic and magmatic processes. It was one of the few historic eruptions to produce a collapsed caldera, voluminous high-silica rhyolite, wide compositional zonation (51-78% SiO2), banded pumice, welded tuff, an on-land ash-flow sheet that supported high-temperature metal-transporting fumaroles, and an aerosol/dust veil that depressed global temperature measurably.Overview of the Eruption

The great eruption of 6-8 June 1912 spanned ~60 hours, in three explosive episodes that produced ~17 km3 of fall deposits and 11±3 km3 of ignimbrite, together representing ~13.5 km3 of zoned magma [Fierstein and Hildreth, 1992]. Episode I released ~70% of the volume, including global plinian ashfall and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes (VTTS) ignimbrite, the enduring fumaroles from which inspired its name. Fallout and ash flows were emplaced concurrently and show identical compositional sequences that extend from 100% crystal-poor rhyolite initially through increasing proportions of crystal-rich dacite and fluctuating fractions of andesite scoria. The ignimbrite is >150 m thick, ranges from nonwelded to densely welded, and was deposited during the first 16 hours as a sequence of compositionally distinct ash-flow packages.

Figure 1. Maps show location of Novarupta, VTTS ignimbrite (yellow), Katmai caldera, and region impacted by ashfall during the 6-8 June 1912 eruption. Dustfall was reported in Virginia by 10 June and in Algeria by 19 June. Ashfall crippled Alaskan ecology and commerce in 1912-13. In 2012, round-the-clock seismic and satellite monitoring by Alaska Volcano Observatory ensures that future eruptions won't surprise us.

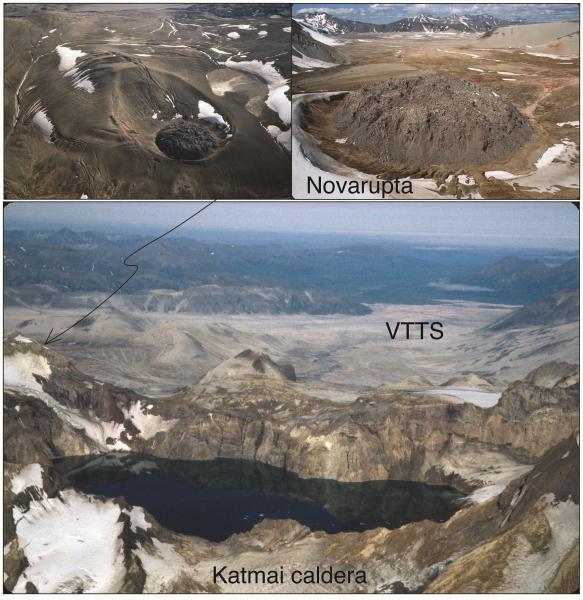

Episode II began after a lull of a few hours and produced 4.8 km3 of dacite-dominant plinian fallout, accompanied proximally by a few sector-confined falls and small pyroclastic density currents. After a short break, Episode III produced 3.4 km3 of dacite plinian fallout, again accompanied proximally by thin andesite-rich falls and minor pyroclastic density currents. All three explosive episodes issued from the 2-km-wide Novarupta depression (Figure 2), which is inferred to be a flaring funnel-shaped vent, backfilled by welded Episode I ejecta and thickly mantled by stratified pumice falls of Episodes II and III. After the final dust layer had settled, a dacite dome plugged the vent and was explosively destroyed and distributed as a block bed. It was soon replaced by a high-silica rhyolite dome (Novarupta, proper), terminating the sequence.

Novarupta lies at the foot of an andesite-dacite cone-and-dome cluster called Trident Volcano, but the eruption broke out through horizontally stratified Jurassic marine sedimentary rocks. Caldera collapse at Mount Katmai (Figure 2), 10 km east of Novarupta, began ~11 hours into the sequence, following release of ~7 km3 of magma. During the next 27 hours, fitful subsidence was accompanied by >50 earthquakes, ten of which were magnitude 6.0 to 7.0 [Abe, 1992], and by phreatic ejections of hydrothermal mud and breccia, which deposited several circum-caldera layers that are interbedded with the contemporaneous plinian pumice-fall layers from Novarupta [Hildreth and Fierstein, 2000]. No juvenile material was expelled from Mount Katmai during subsidence of its kilometer-deep caldera, but a small dacite dome did extrude on the caldera floor soon after collapse. Four additional earthquakes of magnitude 6.0 to 6.9 were recorded in the interval 9-17 June, and lesser shocks were felt for months after the eruption ended (at a village 70 km southwest). Ongoing research at Katmai continues to locate ~1,500 small earthquakes each year and seeks to understand the extraordinary seismic moment release of June 1912.

Volcanological Significance of the 1912 Eruption

The 3-day explosive eruption at Novarupta was the greatest volcanic outburst since Tambora in 1815 and is of enduring interest as one of the five largest in recorded history. For volcanologists and petrologists, the 1912 eruption was extraordinarily provocative, both for what it actually was and for how it was initially misinterpreted in the early days of volcano studies. The fallout was misattributed to Mount Katmai and the ash flows to fissure vents throughout the VTTS. Caldera formation was misattributed to assimilation by the magma or to the mountaintop having been blown off. The "10,000" fumaroles were misattributed to a magma body imagined to underlie the whole VTTS. The varied compositions that erupted together energized the long debate about the relative importance of assimilation vs fractional crystallization, although the striking evidence for mixing of confluent magmas was ignored. The early interpretations stimulated speculative controversy, but no experienced volcanologists visited the remote area until 1953. Since then, global advances in physical volcanology and petrology have gone hand-in-hand with Katmai field studies, clarifying 1912 events and processes and turning the eruption into one of the best studied in the world.

In 1953, Howel Williams and Garniss Curtis concluded that the abundant banded pumice was produced by syneruptive magma mixing, not assimilation, and that the fumaroles had been rootless in the ignimbrite itself, not degassing from a subjacent sill or magma chamber. Curtis later isopached four layers of fallout, showing that each thickened and coarsened toward Novarupta, not Mount Katmai. Recognition that fallout and ignimbrite shared a common vent pointed to column collapse for initiating the pumice-rich ash flows, a model formulated first by Kozu [1934] but widely acknowledged only decades later. Intensive fieldwork later showed the many layers of fallout and nine packages of ash flows to be intercalated and therefore erupted synchronously [Fierstein and Hildreth, 1992; Fierstein and Wilson, 2005], not successively (as conventional models then presumed). Finding that little had erupted at Mount Katmai demanded envisioning some kind of 10-km-long conduit by which magma drained to the Novarupta vent, withdrawing support from the Katmai edifice and inducing caldera collapse.

Figure 2. Aerial view northwestward shows Katmai caldera and ignimbrite-filled VTTS, terminus of which is 29 km from center of caldera. Caldera lake and intracaldera glaciers originated after 1923. Lake is now ~250 m deep, and caldera walls extend 250-800 m above its surface. Novarupta vent depression is dark area on valley floor at left, 10 km west of lake center. Upper panels show rhyolitic Novarupta lava dome (380 m across and 65 m high) within 2-km-wide vent depression, which is backfilled by asymmetrical ring of ejecta and marked by arcuate compaction faults.

Progressive change in rhyolite/dacite/andesite pumice proportions permitted correlation of various ignimbrite facies emplaced contemporaneously, despite differences in initial momentum, in vertical position within density-graded currents, and in outflow distance. Cross-stratified bedsets on near-vent ridgecrests, massive flow units along valley floors, a few thin blast deposits, and the plinian fall deposits all exhibit the same temporal-compositional sequence. This permitted dividing the VTTS ignimbrite into nine distinguishable packages, each consisting of several flow units, successively emplaced over an interval of ~16 hours.

Progressive downvalley deflation, densification, and increasing intergranular friction caused ignimbrite-depositing currents to slow from proximally turbulent to transiently fluidized to distally sluggish grainflows. Laminated ignimbrite and many distal flow units represent not vent-derived currents but features that emerged from massive ignimbrite that was shearing to a halt, stalling, and locally remobilizing in pulses. Welding was rapid where ignimbrite was >100 m thick, promoting valley-axial swales that channelled flow units only hours younger. Crystallization of ignimbrite glass contributed acid gases to the steam-dominated fumaroles and persisted for a decade or longer.

The stratospheric plinian plumes of Episodes II and III resumed hours after the main VTTS ignimbrite sheet was emplaced, contrary to typical explosive sequences. Because compensatory caldera collapse took place 10 km away and reaming of the Novarupta vent entailed only modest marginal slumping, pyroclastic deposits are preserved to within meters of the plug dome (Figure 2), providing extraordinary exposure of the ultraproximal products of sedimentation from the periphery of the plinian jet and lower margins of its convective plume. Within ~2 km of Novarupta dome, sector-confined fall deposits of only local dispersal and thin pyroclastic-density-current deposits are intercalated with the regionally dispersed plinian layers of Episodes II and III. They contribute to overthickened sections of proximal ejecta (Figure 2) and reflect preferential partitioning of andesitic scoria and lithic fragments into an annular collar around the emerging jet, producing transient asymmetrical fountaining and column-margin collapse pulses [Houghton et al., 2004].

Fine ash settles more slowly than coarser fractions of any plinian deposit, and the fines drifted widely in 1912, in directions independent of the SE-trending stratospheric umbrella cloud. Abundant ash was intrinsic to each plinian plume, but some was also swept back up into the column from the circum-vent collapse/deflation zone, and a minor contribution was also elutriated from the VTTS-filling ash flows. A significant fraction of slow-settling fine ash of Episode I was deposited with the fallout of Episodes II and III. The effectiveness of 1912 dust and acid aerosol on cooling the atmosphere was modest relative to many lesser eruptions because the predominant rhyolite, though rich in halogens, was poor in sulfur (which reacts to form long-lived sulfuric-acid aerosol).

The compositional gap between 1912 dacite (63-68% SiO2 and rhyolite (77-78% SiO2) elicited various models for whether the gap originated by secular crystal settling, by ascent of rhyolitic melt from crystal-rich andesite-dacite mush, by partial melting of older wall-rock granitoids, or by some independent source of the rhyolite. Fe-Ti-oxide thermobarometry yields a thermal continuum (800-990ºC) for the 1912 rhyolite-dacite-andesite suite, despite the gap, suggesting contiguity in the magma reservoir. Studies of melt inclusions in quartz crystals from 1912 rhyolite indicate entrapment at pressures of 100-130 Mpa, implying a chamber depth of 3-5 km, as likewise indicated by phase-equilibrium experiments on both the rhyolite [Coombs and Gardner, 2001] and the andesite-dacite compositional continuum [Hammer et al., 2002]. The high-silica rhyolite that dominated the 1912 eruption remains a regional rarity of unproven origin. Its chemical and isotopic similarity to the melt (glass) phase of the coerupted dacite, its thermal and redox continuity with the dacite, and the similar storage depths determined experimentally are all consistent with a compositionally layered magma system. If the rhyolite originated elsewhere, the string of coincidences is remarkable.

Pioneering investigations at Katmai were summarized in a well illustrated book by Robert Fiske Griggs [1922], director of 1915-1919 expeditions sponsored by the National Geographic Society. Our forthcoming monograph [Hildreth and Fierstein, 2012] is a sequel to Griggs' book, updating and amply illustrating a century of progress in learning how volcanoes work and in documenting the complexities and wonders of the great eruption of 1912. For lectures, events, and publications marking this summer's centennial, consult http://www.avo.alaska.edu/ or http://www.nps.gov/akso/index.cfm.

References

Abe, K. (1992), Seismicity of the caldera-making eruption of Mount Katmai, Alaska, in 1912, Bull. Seismol. Soc. Amer., 82, 175-191.

Coombs, M.L., and J.E. Gardner (2001), Shallow-storage conditions for the rhyolite of the 1912

eruption at Novarupta, Alaska, Geology, 29, 775-778.

Fierstein, J., and W. Hildreth (1992), The plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Katmai

National Park, Alaska, Bull. Volcanol., 54, 646-684.

Fierstein, J., and C.J.N. Wilson (2005), Assembling an ignimbrite: Compositionally defined eruptive packages in the 1912 Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes ignimbrite, Alaska, Geol. Soc. Amer. Bull., 117, 1094-1107.

Griggs, R.F. (1922), The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, 340 pp., National Geographic Society,

Washington, D.C.

Hammer, J.E., M.J. Rutherford, and W. Hildreth, (2002), Magma storage prior to the 1912

eruption at Novarupta, Alaska, Contrib. Mineral. Petrol., 144, 144-162.

Hildreth, W., and J. Fierstein, (2000), Katmai volcanic cluster and the great eruption of 1912, Geol. Soc. Amer. Bull., 112, 1594-1620.

Hildreth, W., and J. Fierstein, (2012), The Novarupta-Katmai eruption of 1912: Largest eruption of the twentieth century: Centennial perspectives: U.S. Geol. Surv. Prof. Paper, in press.

Houghton, B.F., C.J.N. Wilson, J. Fierstein, and W. Hildreth (2004), Complex proximal

deposition during the plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Alaska, Bull. Volcanol., 66,

95-133.

Kozu, S. (1934) The great activity of Komagatake (Japan) in 1929, Tschermaks Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittheilungen, 45, 133-174.

Author Information

Judy Fierstein and Wes Hildreth

USGS Volcano Science Center, Menlo Park CA;

E-mail: hildreth@usgs.gov